rm -rf ~

I’m sharing a very important story with you all today. This is the story of a mistake I made–and a mistake that I hope you will never make.

Stay with me, whether you are a programmer or a person, because one day it may save you some heartbreak.

This story starts with where I’ve been in the past seven months, or in other words, what I’ve been doing instead of writing blogs about coding. I’ve been coding–a lot!–but I’ve also been doing math and sewing.

(That’s a weird combination! What are you doing, you ask?)

I’m working on Bra Theory, an empathetic and mathematical approach to better-fitting bras.

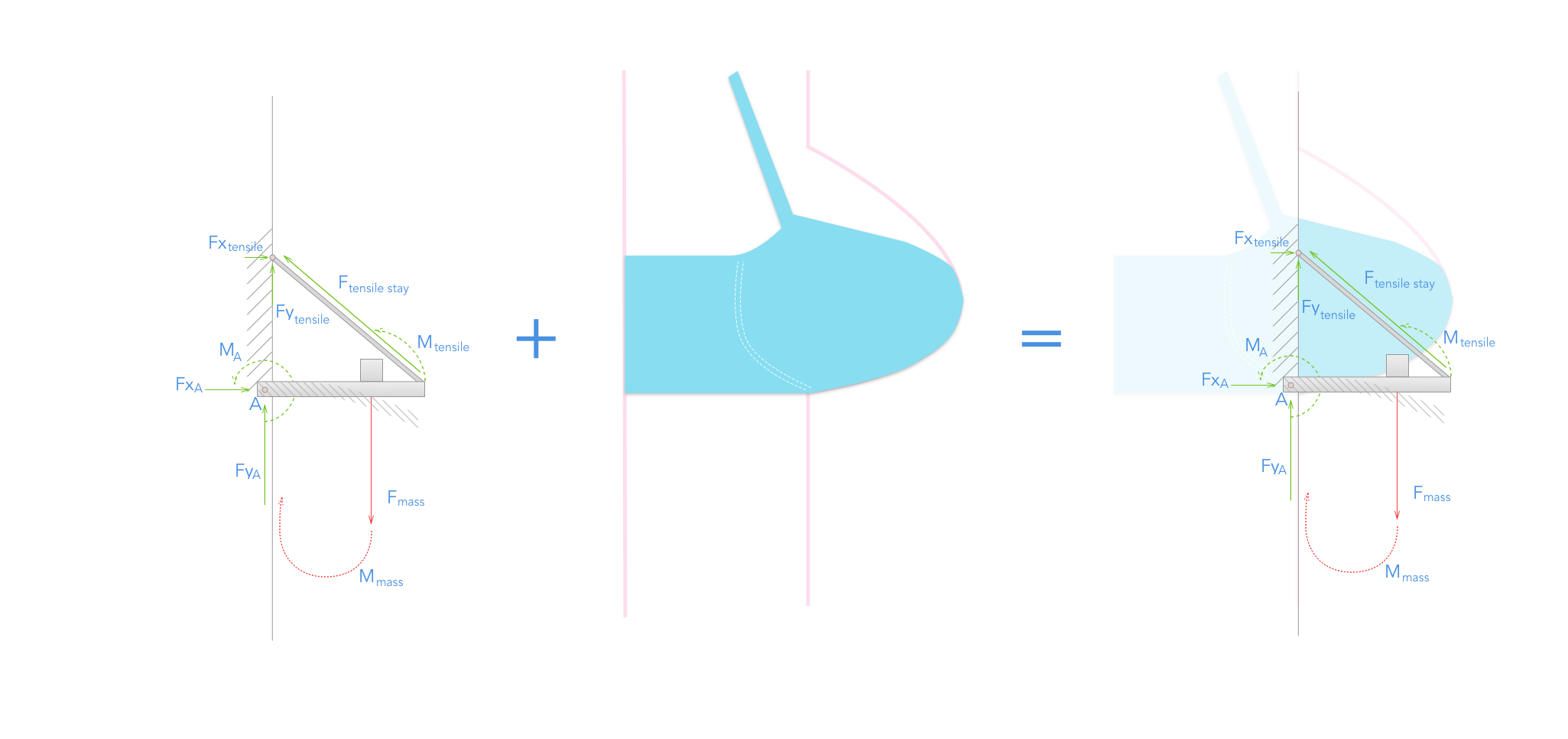

For those of you who have never thought about the function of bra, allow me to give a brief explanation. Bras are amazing feats of engineering that function to encapsulate, support, and shape breast tissue. It’s basically a cantilever, and then on top of that, the base of the cantilever also perfectly approximates the contours of your breast tissue so that it does not result in bulges or gaps. Bras are super functional!

Functional. Magical. This is what a bra was meant to be.

Functional. Magical. This is what a bra was meant to be.

Today, we’re given two variables–band size, cup size–to find a bra that functions. It’s really hard. What if your shoulders are narrower than the manufacturers expect? What if your breasts are set closer than the average width of the bridge? Here at Bra Theory, we want to make you a better-fitting bra – one that fits your unique body.

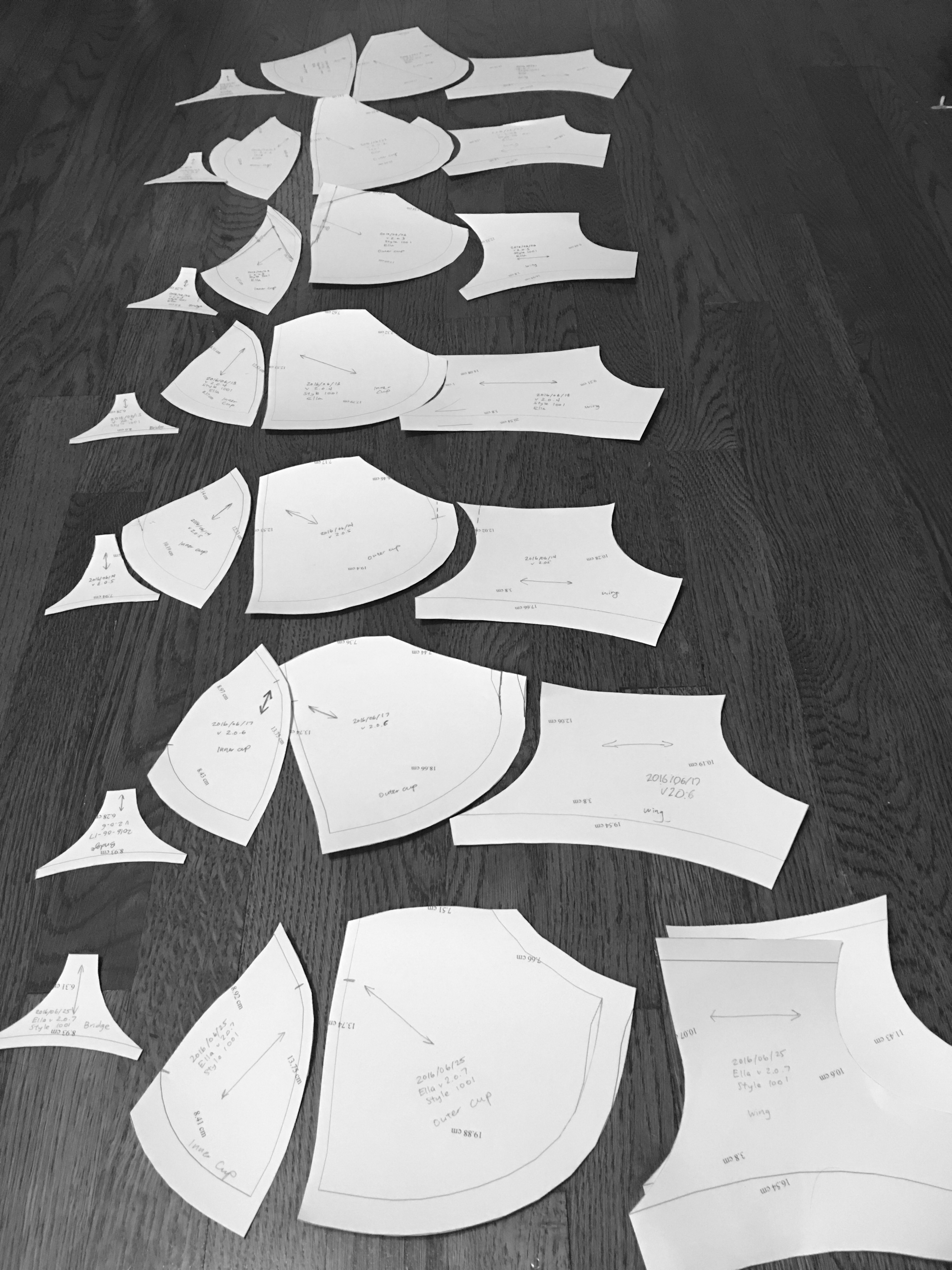

As part of our approach, I’ve written a Python script to generate patterns, or what seamstresses call the 2d model or design for sewing products. Every shirt you wear has an underlying pattern. Every bra you wear–well, not the foam ones, because they’re pressed from a mold that may or may not respect your unique contours–has an underlying pattern. They look like this:

Iterate, iterate, iterate. We’re on 2.0.7 and this fits me pretty well!

Iterate, iterate, iterate. We’re on 2.0.7 and this fits me pretty well!

To generate these patterns, I run a script in the command line (that’s the black box with green text you might see in a movie):

python generate_pattern.py

which reads in a bunch of measurements and writes out patterns to image files. The script takes a little while to run because of all the math it’s doing, so I alt-tab a lot. In the course of something like 30 seconds, I have what I need to make a well-fitting bra! Cool!

What was not so cool was that these image files were cluttering my project and getting dumped to version control. I didn’t want to keep track of every single pixel change. Throwing them on Git seemed like the lazy thing to do.

So I rewrote the script to take a command line argument, or something you can specify by typing in the terminal. Now I could specify the name of a directory:

python generate_pattern.py DIRECTORY

so that the image files were written there, instead of cluttering my Git repo.

I ran my script in Pycharm, which I use as my integrated development environment (IDE – think of it as a text editor with lots of functionality), using the argument ~/Desktop/tmp. ~ usually refers to your home directory. If you type:

echo ~

into your terminal, the command line will output something like:

/Users/mona

That’s ~. That’s your home directory, and mine. That’s where all my other files were located: Desktop, Documents, Pictures… Running python generate_pattern.py ~/Desktop/tmp should have created a temporarily folder /Users/mona/Desktop/tmp.

What I wanted:

/Users/mona/Desktop/tmp

What I got:

/Users/mona/code/bratheory/~/Desktop/tmp

I was in the middle of an alt-tab when I noticed the mistake. Naturally, I wanted to delete the folder. ~ was not showing up in my finder, so I decided to do it the old-fashioned way. I quickly alt-tabbed to my terminal, and without thinking, typed:

rm -r ~

(Please don’t do this at home.)

rm means remove, and -r is an option to recursively remove in case you are removing a folder and its contents.

Do you remember what I said about ~ usually referring to your home directory?

Well, it’s still true.

Let me reiterate.

rm means remove. -r recursively removes a folder and its contents. An unquoted ~ is the name of your home directory, even when you have a subdirectory in your current directory called ~. To refer to the subdirectory, you want \~ or '~'.

A message flashed onto my terminal.

override r–r–r– mona/staff for SOME_FILE_NAME?

It was then that I realized what I had done.

I was in the middle of deleting my entire home directory. Only by chance did I hit a write protected file that stopped to ask me a question (if I had typed rm -rf, I would have been blissfully ignorant until my home directory was empty).

I hit CTRL+C to cancel. I frantically Googled what to do. I shut my Mac down.

You see, typing rm -r ~ is the equivalent of dragging and dropping everything you have to Trash, and then emptying it.

Your computer might still have the data, but it deletes all references to your files. Any subsequent use of the computer might write to those now “empty” spaces.

I had no backups. I had pushed a commit to Git in the morning, so I was missing about three hours of work in terms of my code base. I probably lost all the photos and screenshots of Bra Theory that I had been keeping for future blogs.

I’m going to get overdramatic as I tell you about that day. It’s pretty embarrassing, but I want you to know what it was like, because we all make mistakes, feel bad about ourselves, and feel too bad to tell anyone about it.

The rest of that day was a blur. I was sad. I was ashamed. I may have cried. I never wanted to type in the command line again. The command line is a powerful thing. Not everyone uses it, and for good reason–it’s much harder to drag and drop all your files into the Trash icon, right click, and empty.

I felt unworthy of its power.

My boyfriend, Rajib, came home that night to find me curled up on the couch. I asked him what to do. He is a command line wizard, and I thought he might be able to save me in my time of need.

Instead, he asked what I thought was a cruel question:

“What would you do if those files were gone? Do that.”

But I wanted them back. I wanted the files not for the files, but because I wanted to have not done something so stupid. I wanted to go back in time so that I didn’t have to admit that I was someone who would type rm -r ~ into the command line. I grieved for my lost files–and even more than for my files, for my lost pride.

That night, I thought about what I could have done, and what I could do in the future.

- What if my script didn’t take half a minute to run, so that I wasn’t alt-tabbing and lacking focus?

- What if I used

rm -i, which prompts for each deletion? - What if I just never type

rm -ragain, and insteadmvfiles to a trash folder before performing destructive actions? - What if I used

rmdir, which only removes empty directories?

I could have done all those things, and I can do that in the future. Still, if there had been a spontaneous laptop fire instead of a slip of the keyboard, the result would have been the same.

I began to wonder: even if I had a backup of everything on an external hard drive, or a backup on the cloud, would it be safe?

Everything was, in the end, a physical thing in this world. Even the words that I typed into my terminal, and the words that I offered in abstractions of software, were bits of data on a disk. That disk was somewhere on a server, in a box amongst other whirring boxes. I came to a conclusion: we can put the things that we hold most precious in boxes in faraway rooms, but in the end, nothing is permanent.

I came to a second conclusion. Maybe nothing is permanent, but the only thing that brings us closer is our persistence to make, to write, and to commit in the face of impermanence.

A day later, I set up my desktop computer to continue developing Bra Theory. It was an awful setup: a Windows PC that ran Pycharm locally with a remote repo on a Linux virtual box.

A few days after that, I opened my laptop. I had given up on the disk recovery options. I don’t know what I lost, but I still have my photos, screenshots, and three hours of uncommitted code. I had already rewritten the lost-and-now-found code on my desktop, and probably got it to a better state than it was the first time around.

It was odd, not to know what I lost. I did know that I lost my bash profile, which used to have a tiger and cookie emoji in the prompt. I mourn the loss of my tiger and cookie.

I admitted my mistake to a lot of people afterwards. It was embarrassing, but nice to be vulnerable. People open up to you, too. You begin to learn that everyone makes mistakes.

One person admitted that he had aliased rm to rm -rf for ease of use.

Another admitted that he used rm for a symlink to the home directory.

So, what can you learn from all of this?

I’m not here to tell you, “don’t type rm -r ~” or “use rm -i because it will prompt you for deletions”. Those are tips and tricks that might save you a heartache or two, but that isn’t the lesson of this story.

There are many ways to delete your home directory, and only one way to try to fend off the mortality of human works. My one mistake was:

I didn’t have a backup.

Please backup your files. It doesn’t matter if you don’t use the command line–think about electrical fires, hard drive failures, and the transitory nature of everything. Please back up everything that you hold dear.

And even when you do, don’t feel too bad about losing material things. That’s what life is about. The second lesson of the story:

Nothing lasts forever, except for the work that you do in the moment.

Thanks for reading. R.I.P. 🐯🍪, 2014-2016.